April 11, 2019

Belligerent landscapes. Photo by Irish photographer Michael St. Maur Sheil, taken from a bird’s eye view, one can see a field in Beaumont-Hamel commune of Some Department in France. This scenery resembles a tree leaf under a microscope, or a winding river, or scars and scattered craters. The latter is close to truth: these are scars and craters on the body of our planet – traces of the notorious Somme Battle of 1916, one of the some battles of World War I that lasted for 4.5 months. The scars are the trenches dug in the land, while the craters are the blown shell holes. Such a landscape, changed due to military actions is called belligerent. One of such most popular heritages of World War I is the Lochnagar Crater in La-Boiselle (Fig. 2, 3).

The history of this crater started from day one of the some battle on the 1st of July 1916, when the British Royal Engineering Regiment company mined the shaft under the German fortification wall of Swabia Hills. The early morning blast made a 100 metre diameter and 30 metre deep hole (other sources show 21 metres).

The history of this crater started from day one of the some battle on the 1st of July 1916, when the British Royal Engineering Regiment company mined the shaft under the German fortification wall of Swabia Hills. The early morning blast made a 100 metre diameter and 30 metre deep hole (other sources show 21 metres).

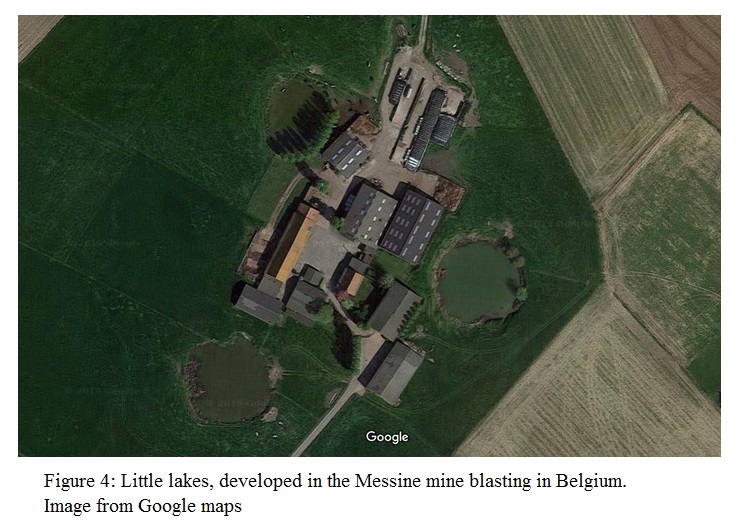

Another notorious example of World War I tunnel war was the Messina Battle, which significantly changed the Western Flanders landscape. We are talking about blasting of underground mines near Belgian town of Messines in June 1917. The Messines operation preparations had started long ago. It had taken 15 months of work for 20 thousand soldiers to build 25 chambers filled with 450 tons of explosives and develop 7.5 kilometres of tunnels at depths to 38 metres. The blasts created 19 craters at diameters to 80 metres. For the ecosystem, such disturbance of associations inside the natural-territorial complex turned out to be fatal: the mines, installed below the water-bearing horizon broke the water resistant layers; ground waters flowed up to the surface, quickly filled the new craters, and caused marsh formation in the area (Fig. 4).

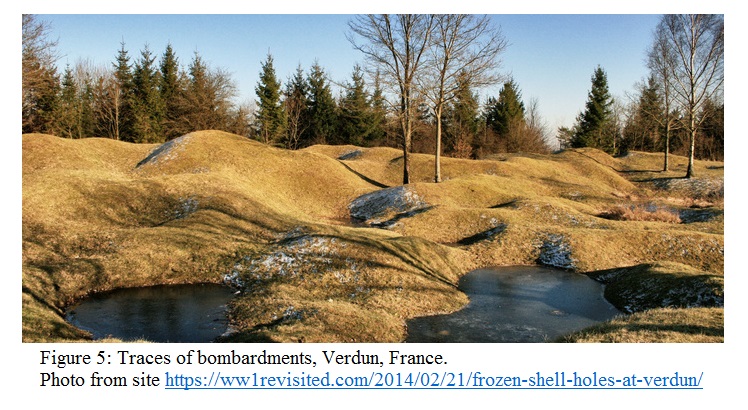

The outskirts of the French town Verdun also suffered significant man-caused damage during World War I during the Verdun battle. It saw battles for almost twelve months, about 60 millions of shells and bombs fell onto a small land at frequency of 5-6 shells per square metre. This resulted in absolute change of the sceneries of northeastern France with all associated disturbances: severe degradation of vegetation cover, reduction of fauna, change of ground water regime, and marsh formation of the land (Fig. 5).

The outskirts of the French town Verdun also suffered significant man-caused damage during World War I during the Verdun battle. It saw battles for almost twelve months, about 60 millions of shells and bombs fell onto a small land at frequency of 5-6 shells per square metre. This resulted in absolute change of the sceneries of northeastern France with all associated disturbances: severe degradation of vegetation cover, reduction of fauna, change of ground water regime, and marsh formation of the land (Fig. 5).

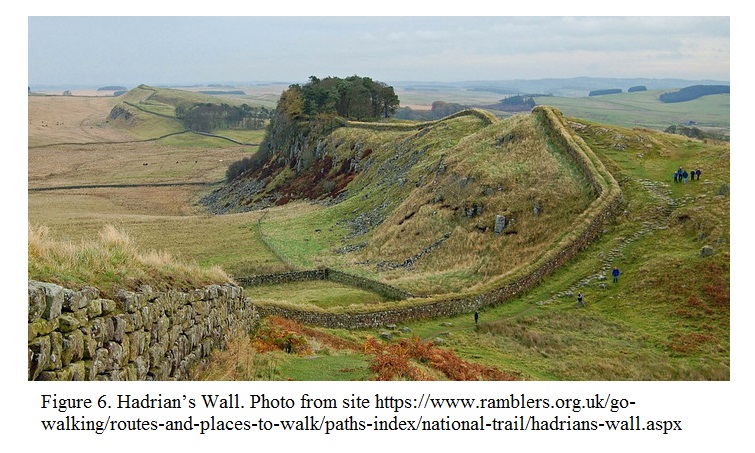

If we bear in mind the fact that the history of humanity is the history of wars, then chronology of landscape transformation positively correlates with the chronology of local and global collisions. The Hadrian’s Wall in Britain is one of the most notorious preserved ancient memorials of wars – a Roman Empire heritage. This defence fortification, built in II century in the north of England was supposed to protect the Roman settlements from the Picts and Brigantians. This defensive erection was a 117 kilometre long stone and turf dump from the Irish to the North Seas. The disturbed vegetation communities have successfully recovered by our times and the territories do not differ from the adjacent plains of the northern England (Fig. 6).

In Russia, there are lines of defence erections that are known as abattis. They were built from felled trees in flat areas of desert watersheds, where the attacking side had not natural obstacles. The Tsaritsyn Watch Line (or Anna Ioanovna Dump), erected from 1718 to 1720 and defended the area between the Volga and Don Rivers from the nomads and Crimea Khanate attacks, became one of such abattis. The 54 km fortified line consisted of a 6-8 metre wide dry trench and a 2.5-4.5 metre high dump embankment. Initially the locality was covered with desert vegetation communities, which significantly degraded after the construction works: the rare trees on slopes and watersheds disappeared, the sols with grass stand was eroded and became practically lifeless to sharply contrast with the surrounding sceneries (Fig. 7)

In Russia, there are lines of defence erections that are known as abattis. They were built from felled trees in flat areas of desert watersheds, where the attacking side had not natural obstacles. The Tsaritsyn Watch Line (or Anna Ioanovna Dump), erected from 1718 to 1720 and defended the area between the Volga and Don Rivers from the nomads and Crimea Khanate attacks, became one of such abattis. The 54 km fortified line consisted of a 6-8 metre wide dry trench and a 2.5-4.5 metre high dump embankment. Initially the locality was covered with desert vegetation communities, which significantly degraded after the construction works: the rare trees on slopes and watersheds disappeared, the sols with grass stand was eroded and became practically lifeless to sharply contrast with the surrounding sceneries (Fig. 7)

XX century saw development of plant and equipment and expansion of belligerent landscape scales. Production of heavy duty caterpillar equipment, which broke the land surface and killed most fertile top horizons of soils, the aviation bombing, new artillery equipment with large calibre shells that broke the land surface and formed dozens of metre wide pits – all this considerably disturbed the lithogenic base (geological structure and relief of landscape) of locations, where military actions occurred, while the high degree impact and the amount of metals in the land made recovery of natural landscapes actually impossible. Poor regeneration of territories meant reduction of arable lands and pastures.

In the second half of XX century, development of chemical industry stepped to a new level, which caused a new type of wars – ecological wars. The most evident example of landscape transformation was the Vietnam War, when American troops actively used spraying of Agent Orange defoliant and blanket-bombing. Some 72 million litres of the substance were spilled to the South-Asian forests to make it easier for American troops to detect partisans and Viet Cong divisions. In addition, use of bulldozer clusters was practiced to remove and kill the top soil horizons, ruin the irrigation networks. As a result, valuable evergreen mangrove forests were completely ruined (500 thousand hectares), 60% of rainforest jungle (about 1 million hectares) and 30% of plain forests (100 thousand hectares) was polluted, incomparable damage was caused to agriculture.

As a result of this, usual belligerent landscape in Vietnam in early 1970s looked like this (Fig. 8).

Global man-caused transformation of landscapes has led to contamination of watercourses and water bodies, disruption of water runoff, soil pollution, and destruction of vast areas of vegetation communities. It also led to subsequent cause of many types of diseases of local population, mass loss of cattle and wild fauna.

Global man-caused transformation of landscapes has led to contamination of watercourses and water bodies, disruption of water runoff, soil pollution, and destruction of vast areas of vegetation communities. It also led to subsequent cause of many types of diseases of local population, mass loss of cattle and wild fauna.

Belligerent landscapes develop even in peaceful times and sometimes even near large cities. Military training grounds represent this type of "peaceful" landscape

Author: Maria Yalbacheva

Source: https://elementy.ru/kartinka_dnya/864/Belligerativnyy_landshaft

Translated into English be Muhiddin Ganiev