February 20, 2023

The Battle for the Memory of Copernicus: Poland vs. Germany. 550 years have passed since the great astronomer, who established the place of our planet in the Solar system was born. "He made the earth move, and the Sun and the sky rise" - this inscription (in Latin) adorns the pedestal of the monument to Nicholas Copernicus in his hometown Torun, in present-day Poland. Even though modern science agrees only with the first part of this statement, the contribution of the astronomer, who came to this world on February 19, 1473, to the development of humankind’s vision of the Universe is indisputable. Like many scientists, having spent years as the administrator of temple properties on the German-Polish border, Copernicus' life was not eventful. Paradoxically, more of such events occurred after his death, when his two homelands - by ethnic origin and citizenship - entered into a dispute among themselves.

Torn Copernicus

Torn Copernicus

The facts about the Copernicus' life, as if on purpose, have reached us in such a way that they tie him almost equally to either German or Polish lands. The surname Copernicus itself is Slavic, but his father, Nikolai Copernicus Sr., died early and had almost no influence on his son. Among the family hey spoke German - the native language of all relatives, including his uncle, Lukasz Watzenrode, who eventually took the cathedra of Bishop of Warmia on the Polish Baltic coast. Not without his help, his nephew went to study in Bologna, where he enrolled in the German community. But in Padua, where he also lived as a student, he declared himself a Pole.

German culture prevailed in the three small towns where Copernicus spent his adult life. But since the middle of the XV century they were under the Polish-Lithuanian state. Within its borders, Copernicus performed representative functions - he served as an envoy of the Bishop of Warmia to the Seym and the king. But he regularly performed in the same capacity at the court of his nearest neighbour, the German-Prussian monarch. Being far from home, Copernicus corresponded with relatives and worked on treatises from various knowledge fields - all of which, like astronomy, served him only as a way to spend his free time. These essays were written in Latin, and he wrote letters in German. But it is also known from the correspondence that Copernicus also had a good command of the Polish language.

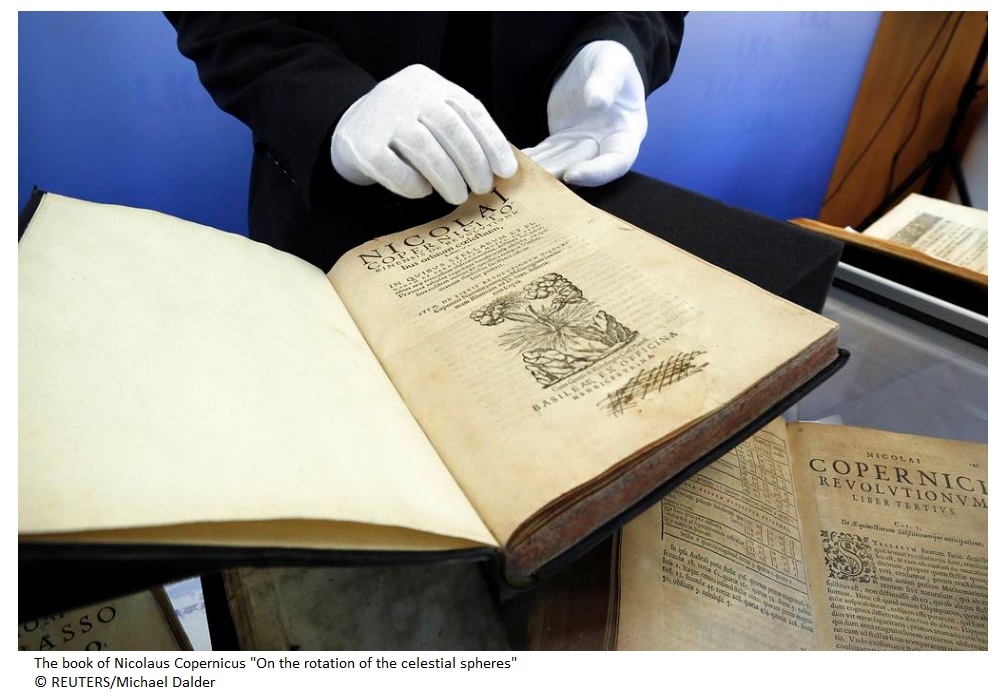

His move to the town of Frombork on the Baltic Sea became a milestone in the history of astronomy of the XVI century. Having taken up the position of a priest in the cathedral, the scholar got one of the towers at his disposal, where he equipped an observatory. In 1530, his main book, "On the Rotation of the Celestial Spheres," could not yet be declared or published. But Copernicus had already finished it, although he was afraid to publish it. The heliocentric system, which placed the Sun at the centre of the universe, contradicted the prevailing ideas about nature in the Catholic Church. But the astronomer lost all his doubts owing to his observations of celestial bodies and mathematical calculations.

In his book, he rejected the hypothesis of the rotation of planets around the Earth in orbits, which allegedly were broken and difficult to calculate, in favour of a clearer model of elongated circles — ellipses. If the Sun itself is put at the centre of the Solar System, contradictory and scattered observational data would converge into a convincing and intelligible scheme. For 13 years Copernicus was wary of making it public and did it only in 1543, and he died shortly after this event.

Astronomical magnitude

A modest church minister and a frankly second row diplomat would be amazed to learn that after his death, a battle for the legacy he had left would commence between Germany and Poland. But before the fight began, the scholar's ideas still had a long way to make their way to recognition. The 1543 edition of the book was a limited one. But this did not prevent its inclusion in the list of Catholic Church banned works. In the XVII century, there was a "war against books" between the supporters and opponents of heliocentrism: the work on the rotation of the celestial spheres was published in large editions, but where the Catholic authorities (in Europe, the wars between Catholics and Protestants) could suspend their distribution, they did so. The reconciliation of the church with the place of the Sun in the universe occurred belatedly only in 1757, and the withdrawal of the famous treatise from the forbidden books list - even later — in 1822.

By this time, Polish Catholics and Bavarian Catholics had already entered into a dispute over the right to be considered Copernicus' compatriots. In 1830, a monument to Copernicus was erected in front of the Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, to which the Bavarian town of Regensburg responded by including the astronomer in the "Valhalla" memorial complex — an expanded collection of German celebrities. It is worth to note that none of these cities had ever been honoured by Copernicus with his presence.

The formation of Polish and German national historiographies continued recklessly on the opposite courses. In the XIX century, the German biographer of Copernicus, Leopold Prowe, did everything in his power to justify the Germanicity of his hero. The slack was picked up by the XX century historian Georg Bender, after becoming the mayor of Breslau (Wroclaw): "The greatest son of the German eastern borders and the special pride of his Prussian homeland," he wrote, meaning that the city of Torun (Thorn) had still belonged to the Germans 19 years before the birth of Copernicus.

Poland, traditionally lacking internationally recognized geniuses and a corresponding self inferiority complex, were quick to return the debt. In the XX century, there was a real boom of Copernicus on Polish lands, which got stronger owing to the independence in 1918. To date, several hundred schools across Poland and countless streets have been named after the astronomer: they claim that there is a topographic site in honour of Copernicus in literally every corner of Poland. Germany achieved a more modest result: there are about a dozen Copernicus streets, but there is a scholarship in his name.

Poland, traditionally lacking internationally recognized geniuses and a corresponding self inferiority complex, were quick to return the debt. In the XX century, there was a real boom of Copernicus on Polish lands, which got stronger owing to the independence in 1918. To date, several hundred schools across Poland and countless streets have been named after the astronomer: they claim that there is a topographic site in honour of Copernicus in literally every corner of Poland. Germany achieved a more modest result: there are about a dozen Copernicus streets, but there is a scholarship in his name.

The battle continues

The tragic events of the Second World War also affected Copernicus, although this happened only by a fortuitous coincidence. In the astronomer the Nazis saw a true Aryan and an exponent of the German spirit. Therefore, on the 400th anniversary of the work on the movement of the celestial spheres - in 1943 - they planned a pompous celebration of the "German jubilee". Neither failures at the front nor unrest in Poland, where the people had already started preparations for the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, prevented this event from taking place. But when it started to happen, it turned out that the Nazis' faith in the Germanicity of Copernicus was always undermined by doubts. In taking revenge on the Poles, the Nazis found nothing better than to throw off the Copernicus' monument in Warsaw and take it away for melting. Fortunately, they failed to complete their plan on time, and in 1945 the monument was already solemnly erected back.

In the defeated Germany, which was divided into east and west, the belief in the Germanicity of Copernicus gradually waned, although books written in this sense continued to be published, as evidenced by a German article in Wikipedia, where Prussia is shown as his place of residence. But over time it became clear that for Poland the great astronomer was more important, and the Germans felt embarrassed in defending their national feelings. This was most clearly manifested in 2008, when Warsaw challenged plans to name the European Earth remote sensing program Kopernikus (that is, Copernicus in the German writing) and demanded to take the same word, but write it down differently. Adam Belan, a European Parliament member from the Law and Justice Party (this party is in power these days), went as far as reproaching the European Commission for "falsification of history."

In fact, the motives of the bureaucrats were much simpler: a firm called Kopernikus was one of the contractors of the project. But Warsaw refused to take into account the business nuance. The uncompromising attitude of PM Belan found sympathy with the vice-president of the Academy of Sciences, who discovered a German "challenge to the Polish great astronomer" in the events that were happening. The Brussels tried to evade the proceedings. However, in 2016 it became known that the Poles had won: a decision was taken to abandon the spelling of the same name that did not suit them. Thee erased the first letter "K" and now they write Copernikus, which corresponds to the English writing rules, despite the fact that the UK has left the European Union.

The European media conciliatorily reacted to the surge of nationalist passions around Copernicus. Experts at German newspapers agreed that establishing the nationality of a person who had lived in the XVI century does not make much sense - the then ideas about citizenship and borders seriously differed from the current rules, in addition to that - preaching an ethnic discord in the XXI century is indecent. A noble reaction and a restrained language - but these did not prevent Europeans and Americans from renaming Russian cultural figures into Ukrainians (like Armenian Aivazovsky and Greek Kuindzhi), by inflating passions, constructing claims, which did not advance before, and completely ignoring obvious historical circumstances.

Source: https://nauka.tass.ru/nauka/17069971

Translated in English by Muhiddin Ganiev