June 14, 2016

Western US wildfires in an increasingly warming climate

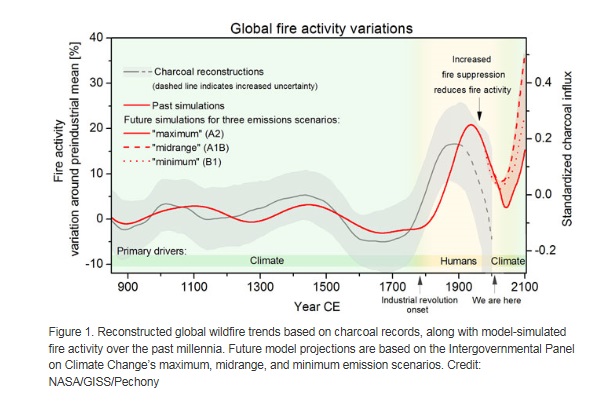

Higher temperatures and severe droughts will likely lead to more wildfire activity in the most vulnerable section of the country. Wildfires have been around as long as there have been terrestrial plants—some 420 million years. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution during the 18th century, fire activity surged across much of the Northern Hemisphere; humans thus became the dominant driver of wildfires. Fire suppression techniques developed at the beginning of the 20th century helped decrease global wildfire occurrence and protect human infrastructure and lives. But despite those efforts, the downward trend is set to reverse. The cause: anthropogenic climate change.

Recent research suggests that the forests of the western US will particularly suffer. Annual temperatures for the region will likely rise between 1 °C and 8 °C by the end of the 21st century, according to climate simulations based on the moderate emission scenario developed by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Droughts will get longer and drier, which will prolong wildfire season. Some studies suggest that the upward swing in fire activity in the western US has already begun.

Despite human mastery of fire as a tool to achieve economic and ecological gains, fire still remains unpredictable. Although fire suppression techniques, combined with extensive agricultural expansion across the western US, have reduced the frequency of large wildfires, those strategies have also resulted in forest structure changes. For example, a significant amount of biomass has accumulated on the forest floor.

Charcoal records, presented in figure 1 alongside climate model simulations from NASA, show that global fire activity has decreased in frequency since the 1920s, likely as a result of wildfire management practices and land use changes. The downward trend of fire activity through the first half of the 20th century also applies to the western US. According to annual fire reports from the US Forest Service, fire-burned area dropped by up to 50% between the early 1900s and 1960.

However, future climate model projections suggest that wildfire activity is unlikely to continue decreasing through the end of the 21st century. Anthropogenic climate change is projected to increase global average temperatures by 2 °C to 7 °C by 2100, which would result in more arid conditions and possibly an escalation in wildfire activity. Although there is still some uncertainty in future precipitation distributions across the western US due to climate change, rising temperatures are a certainty.

As a result of a warming of 1–8 °C, many regions across the western US, including the Rocky Mountains, the Cascade Range, the Snake River Plain, and the Columbia Plateau, will see extended drought conditions during the summer. Extended drought and warmer temperatures will potentially result in less snowfall during the cold season. Since many regions across the western US have their dry season during the summer months, they rely on late spring and early summer snowmelt as a source of water. Increasing temperatures promote earlier snowmelt, which will extend the dry season and prolong the western US wildfire season.

The climate projections in figure 1 suggest that global fire activity will continue to decrease over the next decade or so before increasing again through the end of the 21st century. However, several studies suggest that an increase in fire activity has already begun across the western US, especially across California, as a result of extended drought conditions.

The climate projections in figure 1 suggest that global fire activity will continue to decrease over the next decade or so before increasing again through the end of the 21st century. However, several studies suggest that an increase in fire activity has already begun across the western US, especially across California, as a result of extended drought conditions.

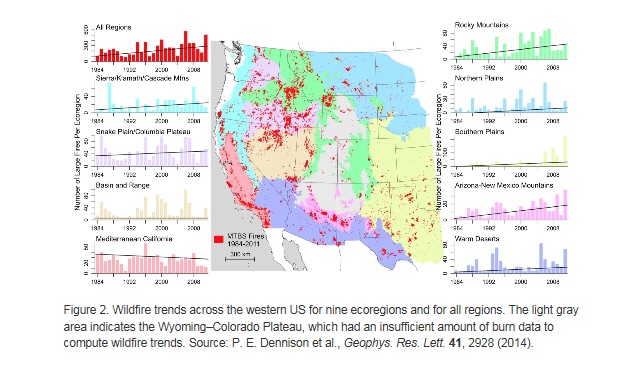

A 2014 study by Philip Dennison of the University of Utah and his colleagues determined that the frequency of large fires increased across seven of nine western US ecoregions from 1984 through 2012 (see figure 2). The Forest Service and the National Interagency F Management Integrated Database also show a general increase in wildfire-burned area across the western US starting sometime in the 1970s. As of early this year, the 2006, 2007, 2012, and 2015 wildfire seasons were the most extensive on record, according to the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho. Last year was a particularly devastating wildfire season, with more than 10 million acres of land burned, which marks the first time that this threshold has been exceeded in recent history. The Okanogan Complex, one of the largest wildfires in 2015 and the largest in the history of the state of Washington, burned more than 300 000 acres of land.

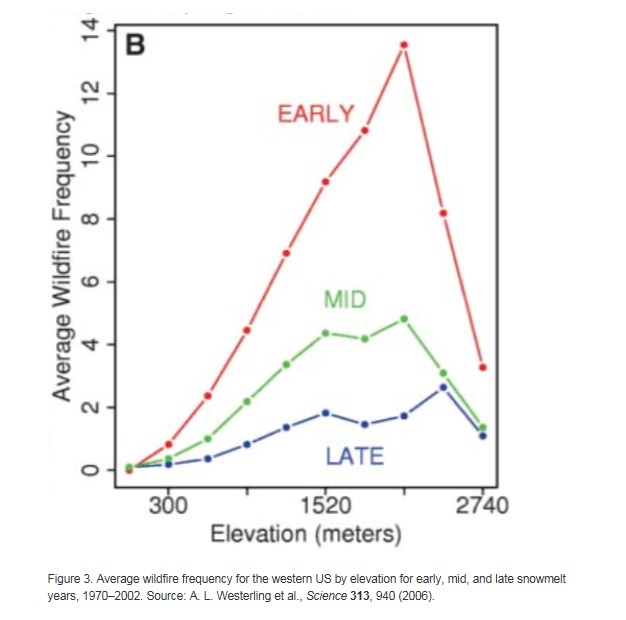

Other indicators reveal a turn for the worse for western US wildfires. A 2006 study by Anthony Westerling of the University of California, Merced, and his colleagues showed that years with increased fire activity are well correlated with seasons with earlier snowmelt during the spring. The work suggests that warming from climate change may already be affecting fire activity across the western US. In fact, the study presents evidence that the average wildfire season length in the western US may have been 64% (74 days) longer in 1987–2003 than it was in 1970–86. Fire activity at higher elevations is most affected by earlier snowmelt (see figure 3), which suggests that those regions are most sensitive to increasing temperatures. Ultimately, those analyses indicate that wildfire trends across the western US may already be past the minimum in fire activity predicted by climate models, with fire activity set to accelerate through the end of the 21st century.

Other indicators reveal a turn for the worse for western US wildfires. A 2006 study by Anthony Westerling of the University of California, Merced, and his colleagues showed that years with increased fire activity are well correlated with seasons with earlier snowmelt during the spring. The work suggests that warming from climate change may already be affecting fire activity across the western US. In fact, the study presents evidence that the average wildfire season length in the western US may have been 64% (74 days) longer in 1987–2003 than it was in 1970–86. Fire activity at higher elevations is most affected by earlier snowmelt (see figure 3), which suggests that those regions are most sensitive to increasing temperatures. Ultimately, those analyses indicate that wildfire trends across the western US may already be past the minimum in fire activity predicted by climate models, with fire activity set to accelerate through the end of the 21st century.

G oing forward, increased wildfire activity across the western US will affect not only human communities but also ecology on regional and global scales. Current studies suggest that forests in the western US sequester 20–40% of the country’s carbon emissions. However, as wildfire trends increase, the burning biomass will emit more carbon dioxide and turn the region from a CO2 sink to a source, making the fight against climate change all the more difficult.

oing forward, increased wildfire activity across the western US will affect not only human communities but also ecology on regional and global scales. Current studies suggest that forests in the western US sequester 20–40% of the country’s carbon emissions. However, as wildfire trends increase, the burning biomass will emit more carbon dioxide and turn the region from a CO2 sink to a source, making the fight against climate change all the more difficult.

Wildfires can also significantly affect air quality in regions downwind of the fires. Smoke plumes—which contain very small particulates and precursors to ozone formation that negatively impact the human respiratory, cardiovascular, and immune systems—can travel for hundreds of miles. More frequent wildfires emitting greater emissions of pollutants across the western US, coupled with population growth, will only exacerbate air quality issues in the future.

With increased warming from anthropogenic climate change projected to continue, the number of wildfires across the western US will likely increase through the end of the century. Unless humans can achieve significant reductions in carbon emissions, the impact of wildfires on communities and ecosystems across the region will continue to magnify.